Following my OMSI Science Pub presentation in February, I was invited to present at the OMSI After Dark event: “It’s Alive (Mind and Body)!” on April 25th!

I’ll be presenting a shorter, 20 minute version on the Microbiome of the Digestive Tract!

Following my OMSI Science Pub presentation in February, I was invited to present at the OMSI After Dark event: “It’s Alive (Mind and Body)!” on April 25th!

I’ll be presenting a shorter, 20 minute version on the Microbiome of the Digestive Tract!

I’m very pleased to announce that I’ll be teaching a course this fall on “Introduction to Mammalian Microbiomes”, with the University of Oregon Clark Honors College. I hope that this will be the first of many courses taught at UO, beginning with my background in “host-associated”, and expanding out into “house-associated”.

The learning objectives of this course are to introduce students to basic concepts in host-associated microbiomes. Some background in microbial ecology, genetics, anatomy, bioinformatics, or immunology would be helpful, but is not required. While difficult concepts will be discussed, the course is intended to teach students about the basic principles: what is a microbiome? How does host anatomy drive microbial ecology? How does that community develop over time? How does it change? How does technology inform our understanding of these systems, and what limitations does that technology introduce? When we read about host-associated microbiomes in the news, especially regarding health, how can we assess if the study is rigorous and how should be interpret the scope of the findings? The skill-set objectives include learning to review complicated journal articles, distilling their findings while understanding their limitations, and developing science communication skills in a variety of formats.

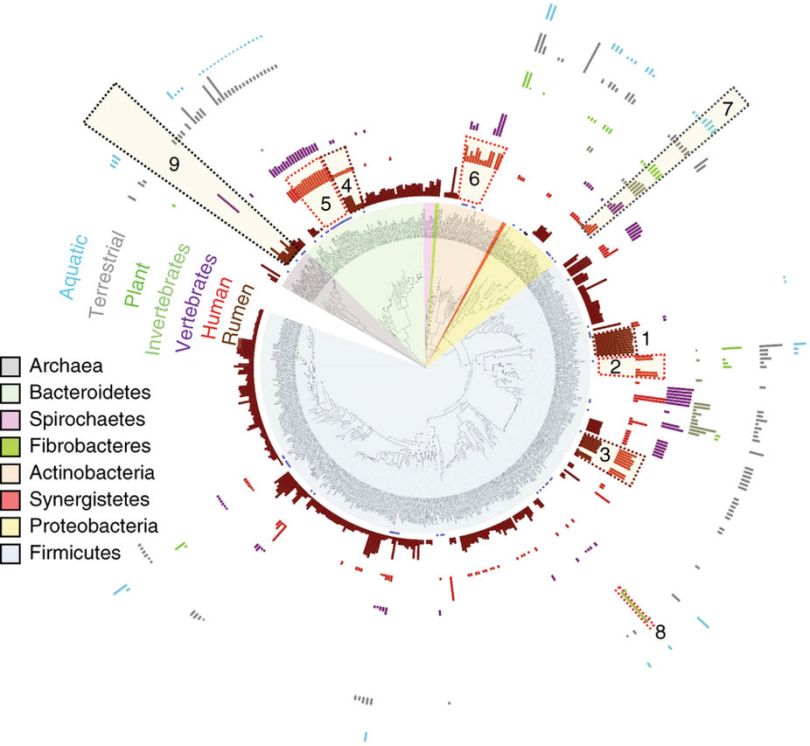

The Hungate 1000 Project was a massive undertaking: namely, sequencing the genome of 1000 microorganisms cultured from ruminant animals all over the world, and was both coordinated and led by the Rumen Microbial Genomics Network. After years of hard work by some incredible researchers, the Hungate 1000 has just been published in the Nature Biotechnology Journal! The […]

This summer, I’ll be presenting a talk at the Indoor Air 2018 conference in Philadelphia, on some of the work I’ve been doing on bacteria in homes!

Biology and the Built Environment Center

For the past two months, I’ve been spending quite a bit of time writing grant proposals. In particular; those which expand our understanding of indoor lighting on human health and behavior, the indoor microbiome, and energy usage in buildings. These project proposals are collaborative efforts between several University of Oregon research labs: Biology and the Built Environment Center, Energy Studies and Buildings Laboratory, and the Baker Lighting Lab. I’ll have more updates in the next few months as those are reviewed.

Siobhan “Shevy” Rockcastle, Chair of the Baker Lighting Lab, and I have been brainstorming ideas, and today I went over to the Baker Lab to check it out in person. The Lab is decorated with concept-design lighting projects from previous students, which are not only beautiful, but extremely creative. Here are a few of my favorites!

Most studies that examine the microbial diversity of the gastrointestinal tract only look at one or two sample sites, usually the mouth, the rumen in ruminant animals, or the feces. It can be difficult, expensive, invasive, or fatal to get samples from deep inside the intestinal tract; however many studies have pointed out that anatomical location and local environmental factors (like temperature, pH, host cells, nutrient availability, and exposure to UV light) can dramatically change a microbial community. Thus, the microbes that we find in feces aren’t always what we would find in the stomach or along the intestines. On top of that, certain microorganisms have been shown to closely associate with or attach to host cells, and the diversity of microbes next to host tissues can be different from what’s at the center of the intestines (the digesta).

This large, collaborative project took samples from nine different sites along the digestive tract of calves over the first 21 days of life to determine how body sites differed from each other, how sites changed over time as the calf matured, and how the lumen-associated bacteria would differ from the digesta-associated bacteria. Samples from the mothers were also taken to understand how maternal microbial influence would affect body sites over time.

This paper was just published in Scientific Reports, and was something I had previously presented on at the Joint Annual Meeting of the American Society for Animal Science, the American Dairy Science Association, and the Canadian Society for Animal Science in Salt Lake City, UT in 2016.

Biogeographical Differences in the Influence of Maternal Microbial Sources on the Early Successional Development of the Bovine Neonatal Gastrointestinal tract. Carl J. Yeoman, Suzanne L. Ishaq, Elena Bichi, Sarah K. Olivo, James Lowe, Brian M. Aldridge. 2018. Scientific Reports.

The impact of maternal microbial influences on the early choreography of the neonatal calf microbiome were investigated. Luminal content and mucosal scraping samples were collected from ten locations in the calf gastrointestinal tract (GIT) over the first 21 days of life, along with postpartum maternal colostrum, udder skin, and vaginal scrapings. Microbiota were found to vary by anatomical location, between the lumen and mucosa at each GIT location, and differentially enriched for maternal vaginal, skin, and colostral microbiota. Most calf sample sites exhibited a gradual increase in α-diversity over the 21 days beginning the first few days after birth. The relative abundance of Firmicutes was greater in the proximal GIT, while Bacteroidetes were greater in the distal GIT. Proteobacteria exhibited greater relative abundances in mucosal scrapings relative to luminal content. Forty-six percent of calf luminal microbes and 41% of mucosal microbes were observed in at-least one maternal source, with the majority being shared with microbes on the skin of the udder. The vaginal microbiota were found to harbor and uniquely share many common and well-described fibrolytic rumen bacteria, as well as methanogenic archaea, potentially indicating a role for the vagina in populating the developing rumen and reticulum with microbes important to the nutrition of the adult animal.

At a conference this summer, I attended a lunch discussion on gender equality in science, and diversity and equity in the workplace in general, hosted by the activist group; 500 Women Scientists. What was planned to be a small meeting of 20-30 women very quickly turned into a standing-room-only event as an unexpected number of women and allies arrived; a momentum which has been gathering since the inception of 500WS. Following the 2016 presidential election, four women decided it was time to act and founded the organization with the goal of getting 500 women in STEM to sign an open letter in support of science. As of writing this, more than 20,000 supporters from over 100 countries have joined the movement, which has sparked a number of actions.

First, 500WS seeks to spread awareness of issues and provide resources towards improving life in the workplace. In particular; recognizing, preventing, and providing justice for sexual harassment in the workplace has been a large focus of the 500WS group, among many other organizations and individuals in the #MeToo movement.

Second, 500WS aims to create gender equality in STEM and the workplace in general, by promoting inclusion, by advocating for employee-friendly practices, and by reducing bias. These policies not only help women, for example; they help working parents of all genders through the implementation of policies like parental leave. One of the 500WS measures is providing an online resource for people to Request A Scientist, to promote the visibility of women in STEM and support their inclusion in news articles, on panels, as speakers, and in leadership positions. This visibility in the media reinforces the idea that women are actively working in STEM, are making important contributions to it, and can help dispel gender stereotypes and bias which lead to pay discrepancies and missed career opportunities. Along with similar resources like the Diverse Sources Database, 500WS seeks to reinforce the idea that scientists come in all sorts of formats.

Third, 500WS is an activist group. In addition to promoting the March for Science movement last year and this year, they regularly post actionable items for women in STEM and supporters on their Take Action Tuesday blog posts. Most recently, 500WS is also launching a Science Salon campaign to raise money for Puerto Rico, which has yet to recover from catastrophic hurricane damage due to insufficient US recovery funds and a lack of media attention.

Those of you following my blog know that I am a firm supporter of equity in science (although largely from the point of view of women in STEM – write what you know, after all); I have debated the existence of the pay gap with others online; I have written about the lack of women in STEM, the disparity between what women are expected to do at work and how their performance is judged, the awkward problem of name changes and publication records, and not missing out on brilliant researchers because of bias; I have hosted a STEM workshop for girls, been a mentor to an elementary student, attended Meet a Scientist day at the Eugene Science Center; and I have marched for science, equality, and human rights when I could.

I am thrilled to announce that I’m also joining the 500 Women Scientists Eugene Pod as a co-coordinator! The Eugene Pod leadership has been working hard to develop a Eugene Science Salon, and we hope to make it a reoccurring event which will promote local women in STEM, increase public engagement and education in STEM, and raise money for a variety of causes.

You can find the Eugene Pod online on Facebook and Twitter and both women in STEM and supporters of any gender, sexuality, ethnicity, nationality, age, career path, field, and preferred Oregon college sports’ mascot are welcome to join. If you are a woman (the inclusive definition of woman) in the Eugene area who would like to join the group and attend meetings to plan larger events, please join our Meetup group.

The national 500 Women Scientists is here: Organization | @500womensci | Facebook

Last night, I gave my first “science stand-up” as part of the Oregon Museum of Science and Industry (OMSI) Science Pub series at Whirled Pies in Eugene, OR. I really enjoy giving public presentations of my work, and while I’ve been on stage with a microphone before, it was the first time I got a stool to put my drink on.

I gave a talk which encompassed much of my previous work on host-associated microbiomes in moose and other ruminants, as well as more current research from others on the human gut. It’s difficult enough to fit the field of host-associated microbiomes into a semester-long class, nevermind an hour (I digress), so I kept it to the highlights: “A crash course on the microbiome of the digestive tract“. You can find the slides here: Ishaq OMSI SciPub 20180208, although there is no video presentation at this time. I was honored to have such a well-attended lecture (about 120 people!) with an engaged audience, who had some really on-track questions about the intersection of microbial diversity and health.

As I’ve discussed here before, academic outreach is a sometimes overlooked, yet nevertheless extremely important, aspect of science. The members of the general public are a large portion of our stakeholder audience, and outreach helps disseminate that research knowledge, facilitate transparency of the research process, and engage people who might benefit from or be interested in our work. As I told the audience last night, scientists do like when people ask us about our work, but “we’re more scared of you than you are of us”. I encourage everyone to add science to their life by getting informed, getting involved, and getting out to vote.

Thanks again to OMSI for inviting me to participate, and to Whirled Pies for hosting!

Featured Photo Credit: Al Lebovitz

Last June, I started a position as a Research Assistant Professor of Microbial Ecology at the Biology and the Built Environment Center at the University of Oregon. The BioBE Center is a collaborative, interdisciplinary research team investigating the built environment – the ecosystem that humans have created for themselves in buildings, vehicles, roadways, cities, etc. With my background in host-associated microbiology, I am concerned with how the built environment interacts with biology.

Humans shed microorganisms constantly – every itch, every cough, every minute. In fact, our buildings are littered with the biological material shed from our bodies and our microbiomes (1, 2, 3, 4). Pets (1, 2) and plants (1, 2) also contribute, and so does outdoor air (1, 2). In fact, the indoor environment is full of microorganisms.

In addition to knowing how our presence, our behaviors (ex. cleaning), and how we run our buildings (ex. ventilation) creates the indoor microbiome, I want to know how the indoor microbiome affects us back. Not only can “sick buildings” negatively affect air quality, but they can harbor more microorganisms, especially fungi, or pathogenic species which are detrimental to our health.

My first indoor microbiome data is one that I have inherited from an ongoing project on weatherization in homes, and hope to present some of that work at conferences this summer. Since June, a large amount of my time has gone into project development and grant writing, most of which is still pending, so stay tuned for details. It has involved read lots of articles, going to seminars, networking, and brainstorming with some brilliant researchers.

As research faculty, I am not required to teach, although I have the option to propose and teach courses by adjusting my percent effort (I would use the teaching salary to “buy back” some research salary). As I am not currently tenure-track, I am also limited in my ability to hire and formally mentor students. However, I have been teaching bioinformatics to a student who recently graduated with his bachelor’s and is pursuing a masters in bioinformatics later this year.

I’ve also been keeping up with my science outreach. I gave a presentation on my host-associated microbiome work, I marched, I volunteered for a few hours at Meet A Scientist day at the Eugene Science Center, and I’m hosting a Science Pub on “A crash course in the microbiome of the digestive tract” at Whirled Pies in Eugene this Thursday, February 8th!

The end of 2017 marks the second year of my website, as well as another year of life-changing events, and reflecting on the past year’s milestones help put all those long hours into perspective. I reviewed my year last year, and found it particularly helpful in focusing my goals for the year ahead.

In the first half of 2017, I was working as a post-doctoral researcher in the Menalled lab at Montana State University, researching the interaction of climate change, farm management (cropping) system, and disease on soil bacteria in wheat fields, as well as the legacy effects on subsequent crops. I am still working to analyze, interpret, and publish those results, and hope to submit several manuscripts from that project in early 2018. In June, I began a position as a research assistant professor in the Biology and the Built Environment Center at the University of Oregon.

This involved another large move, not only from Montana to Oregon, which has led to some awesome new adventures, but also from agriculture and animal science to indoor microbiomes and building science. So far, it has been a wonderful learning experience for incorporating research techniques and perspectives from other fields into my work.

2017 has been another extremely productive year for me. I presented some work at two conferences, the Congress on Gastrointestinal Function and the Ecological Society of America meeting (additional ESA posts here and here). While at ESA, I was able to attend the 500 Women Scientists luncheon to discuss inequality in academia as well as recommendations we could make to improve ESA and other conferences ,such as offering affordable on-site child care, and action items we could take ourselves, such as attending training workshops to combat implicit bias or making sure job searches recruit a diverse candidate pool.

This year, I added four new research publications and one review publication to my C.V., and received word that a massive collaborative study that I contributed to was accepted for publication- more on that once it’s available. In April, I hosted a day of workshops on soil microbes for the Expanding Your Horizons for Girls program at MSU, and I gave a seminar at UO on host-associated microbiomes while dressed up as a dissected cat on Halloween. In November, I participated in a Design Champs webinar; a pilot series from BioBE which provides informational discussions to small groups of building designers on aspects of how architecture and biology interact.

I published 34 posts in 2017, including this one, which is significantly fewer than the 45 I published in 2016. However, I have doubled my visitor traffic and views over last year’s totals: over 2,000 visitors with over 3,200 page views in 2017! My highest-traffic day was April 27th, 2017. While I am most popular in the United States, I have had visitors from 92 countries this year!

My most popular post is currently “Work-life balance: what do professors do?”, with over 610 views! My least popular is “Presentation on juniper diets and rumen bacteria from JAM 2016 available!” with just 2 views, granted, that one appeals to a much narrower audience. This year, in addition to updates on publications, projects, and positions, I wrote about writing; including theses and grants. I wrote about getting involved in science, be it through education, participation, or legislation. I described outreach in academia, and the process of interviewing. I gave some perspective on the effect of climate change and anthropological influence on agriculture and ecology, as well as on the debate surrounding metrics of success in graduate study.

I also added some “life” to my work-life balance; in November, I married my best friend and “chief contributor“, Lee, in a small, stress-free ceremony with some local friends in Eugene, Oregon!!

I have high hopes for 2018, notably, I’d like to finish more of the projects that have been in development over the last two years during my post-docs. Nearly all academics carry forward old projects: some need additional time for experimentation or writing, some get shelved temporarily due to funding or time constraints, some datasets get forgotten and gather dust, and some which got cut short because of the need to move to a new job. This is a particular concern as grant funding and length of job postings become shorter, forcing researchers to cut multi-year projects short or finish them on their own time. After defending in early 2015, I had two one-year postings and started at UO in June 2017, making this my fourth job in three years. I’m looking forward to roosting for a bit, not only to clear out unfinished business, but also to settle into my new job at BioBE. This fall, I have been analyzing data on a weatherization project, writing a handful of grants, and developing pilot projects with collaborators. I have really enjoyed my first six months at BioBE, and Lee and I have taken a shine to Eugene. In the next few months, I hope to have more posts about my work there, exciting new developments in BioBE and ESBL, and more insights into the work life of an academic. Happy New Year!