Outside the academic world, there is a lot of misconception about what faculty and university personnel actually do and when. While this varies by position, university faculty have a variable mix of teaching, research, advising students, grant writing, administration of grant budgets and workloads for persons working in the lab, being on institutional committees (curriculum planning, graduate student committees, candidate search committees), and community outreach (presentations, generating informative publications for the general public, etc.). As universities have sought to increase student populations while decreasing faculty, this has led to an ever-increasing number of hours spent working.

The Academic Ladder

To understand the problem with workloads, we must first understand the positions generally available. It’s taken for granted that graduate students will work more than 40 hours per week. Graduate teaching assistants are paid a stipend to teach a certain number of credits per semester, and generally their tuition is covered by the department they are teaching for, although this does not always include university fees and health insurance. At the University of Vermont as a GTA, I still paid around $1,200 per semester, despite having my tuition and some of my student health insurance comped. As a graduate research assistant, a research grant pays your stipend and, potentially, your tuition. Either way, you are taking classes and expected to do your own research, and it is very difficult to excel at all aspects while try to only work 40 hours per week.

Post-doctoral researchers have attained their Ph.D., and are specializing in an area of research. Often, PhDs go from post-doc position to post-doc position waiting for a professorship in their field to open up. Depending on the positions, post-docs also have to write their own grants, and may have to teach, although this is often unpaid. In 2005, post-docs in the US reported working an average of 51 hours per week, diluting their salary until their effective hourly pay was lower than Harvard janitorial staff. As reported in the study, average post-doctoral salary ($38k/year) was also less than the average salary of someone working outside of academia with only a bachelor’s degree ($45k/year), and much less than those with professional degrees ($72k/year).

From there, a variety of academic positions available, but these generally fall into three tiers: assistant, associate, and (full) professor. For example, if you are a research professor, you do not have to teach and often do not mentor students outside of your graduate students, and you can be at the level of assistant-, associate-, or (full) research professor depending on your years of experience. These are almost always non-tenured positions, meaning you work by contract, and you often have to fund your own salary through grants. There are also adjunct professors, as well as lecturers or instructors. Like research professors, they perform fewer functions (generally just teaching and advising), and have short-term contracts. Adjunct positions are part-time with no benefits, while lecturers are full-time and come with benefits, and their prevalence in research universities is increasing.

Traditional faculty positions, on the other hand, have salaries paired through the department, and are contracted for longer periods of time. You can also be at the level of assistant, associate, or (full) professor, and you may also apply for tenure. Tenure is a permanent contract with the university, and it is a grueling review in which all of your career moves are carefully examined by a panel of your peers. The idea behind tenure is that once it is awarded, you cannot be fired except under special circumstances, allowing you to pursue less trendy and more daring research topics. Tenure is not awarded lightly, and assistant (or associate) faculty spend years trying to accomplish as much as possible, such that they are driven to work longer hours. Faculty without tenure reported working an average of 56 hours per week, which is likely driven by assistant professors that reported working 56 hours per week.

All of these positions may be offered as 9 (September to May) or 12 month appointments, meaning you are only paid for working that many months. There is a perception that faculty don’t work in the summer, and that’s because those 9 month appointments are not required to work. However, most take the opportunity to catch up on research or generating teaching materials, and many academics report working longer hours in the summer. While you might be awarded grant money to pay salary for the three months of summer that you spend catching up on research, many academics will end up working uncompensated just to keep up.

Responsibilities

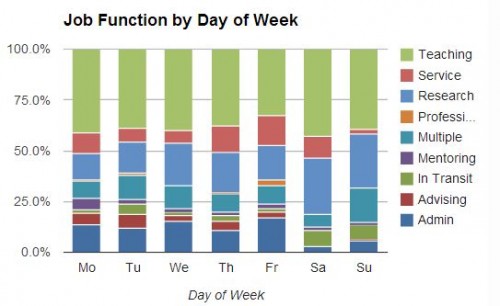

In a preliminary study by anthropologist Dr. John Ziker, called Time Allocation Workload Knowledge Study (TAWKS), 30 professors from Boise State University were asked to recall everything they had done over the past 24 hours. Participants reported an average of 61 hours per week spent working, including about 10 hours on the weekend. The breakdown of their job functions is below:

Other studies report similar findings, with an average 53 hours per week spent on all activities, and a breakdown as such:

This seems to be skewed towards assistant professors:

as well as non-tenured faculty:

As I mentioned, professors are responsible for teaching, research, advising students, grant writing, administration of grant budgets and workloads for persons working in the lab, institutional committees (curriculum planning, graduate student committees, candidate search committees), and community outreach (presentations, generating informative publications for the general public, etc.). Here is a very long list that one professor made of their responsibilities. Enrollment in college has increased over the past few decades, but faculty hires have not kept pace: there are an average of 16 fewer staff members per 1,000 full-time students in 2012 than there was in 2000. While the number of faculty positions in the US has increased numerically, this growth has been overwhelmingly in part-time hires, with a 121% increase from 1990 to 2012 as compared to a 41% increase in full-time hires. The increasing number of students, expansion of faculty responsibilities, and the rise in part-time employees who often travel to multiple universities in a day for work have pushed staff and faculty to work longer hours, yet this does not always translate into better quality of work, as some work functions take priority over others over time.

In the follow-up segment, I’ll discuss the importance of time off and finding a work-life balance (as I write this on evenings and weekends), and how this contributes to reduced stress, as well as improved health, productivity, quality of work, and quality of life.

If you’re in academia, what do you do on a daily basis? Leave me some comments!

[…] her blog, microbial ecologist Dr. Suzanne L. Ishaq shares “Work-life balance: what do professors do?” specifically about the importance of and what it looks like to have a balanced life in […]

LikeLike

[…] but amazing people who have devoted themselves to incredible work. Psychologists who may be juggling administrative appointments (with responsibilities to students, faculty, and institutional …, who likely have major grants (with huge dollars at stake and multiple things to coordinate for […]

LikeLike