This semester at UMaine, I’m teaching a section of AVS633/FSN671 Graduate Seminar, for students in the Animal and Veterinary Science and the Food Science and Nutrition grad programs. Naturally, I decided to spice up the course requirements.

In all the presentations I have given; during classes, teaching, as public lectures, guest seminars, and conference proceedings, I’ve faced a great deal of technical and audience-related challenges. There is a wealth of information on the formatting and content aspects of building a scientific presentation, but in my experience, that’s only half the battle. The other half is in being able to accurately and interestingly relay that information to your audience. Even in professional settings, I have faced disruptive technical failures that caused me to alter my talk or have to adjust my narrative, and I have fielded poorly-crafted or poorly-intended questions from my audience, all while trying to maintain my composure.

I felt that this was what the graduate students needed to learn, and in a safe space where it was OK to simply, well, give a bad presentation. To convey this, I put together an introduction to the class (below) and a series of assignments.

The Elevator Speech

Their very first assignment was to stand up, with notes but no slides, and give a 3 minute speech on a topic of their choice. It had to be non-technical, and designed to provide information in an approachable way such that the person stuck on the elevator with you would actually want to hear more. As academics, especially when you are a student, you often get caught up in repeating jargon or with having to explain yourself in highly detailed language to faculty who are training and testing you. You forget how to present your work to someone who has absolutely no background, and only a few minutes worth of attention span to devote to hearing about your very niche research question. To give an effective elevator speech, the students needed to distill only the critical information for someone to follow their line of thinking, and to not get bogged down by extraneous detail.

Peer Presentations and Awkward Audience Questions

For the second assignment of the course, each student was required to give a presentation on their research, their program of study, or a specific topic they were interested in and the relevant research. Due to the number of students and course time allotted, this presentation only needed to be 10 minutes long, but I’ve found it can be more difficult to present your material concisely. The students presented as if to a peer audience, so they could use a certain amount of jargon or introduce methods with minimal explanation. This style of presentation is common in graduate school, and as expected, the students all did incredibly well.

To add a challenge here, I instead focused on the audience (in this case, the rest of the class). The thing about being an audience member that most people never think about, is that you also need to conduct yourself with a certain level of professionalism. It might not be polite to shout a question or snarky response in the middle of a presentation, your comments might seem complementary but are in fact back-handed, or your question might simply be poorly crafted. I have been asked, or been witness to, a lot of poorly-worded audience questions and responses, and I’m not referring to general public audiences, I’m talking about academics who should know better.

To that end, for each student presentation, I gave an index card to another student in the audience to ask or perform during the talk. Participation was voluntary. Some of these are well-meant questions that are simply commonly asked. Others are silly, and some are rude. I didn’t include anything offensive or abusive, but those examples abound. The list is pretty funny, but please, NEVER DO THESE AS A REAL AUDIENCE MEMBER.

- Ask the speaker if they will be a medical doctor (or veterinarian) after they finish this [research] degree.

- State that you have a question. Then pose a statement/comment that is not a question.

- Be on your phone (texting) or overtly not paying attention to the entire presentation.

- Ask them to explain a simple concept that they covered in their presentation (but that you missed because you weren’t paying attention).

- Cough or sneeze comically loud, or drop something during the presentation.

- Ask the speaker how they chose this topic or how they got into this type of research/work. (This seems benign, but can take away from more specific questions during a peer presentation.)

- Ask if the speaker is familiar with a field/event/discovery that is somewhat related to their presentation but not actually in their presentation. Example, speaker presents about infectious disease in cattle and you ask them about “cow farts and global warming”.

- Comment that the speaker looks really young for someone in their position. Example: “Wow, I thought you were an undergrad! You look really young. I mean, that’s a compliment.”

- Get up during the presentation and adjust the lights or shades in the room. You don’t have to make them better, just change them.

- Ask the speaker a multiple part question. They can be simple questions, but ask them all in one, long, run-on sentence.

- Begin your question with “As a parent,….” even if you are not a parent and the question has nothing to do with being a parent.

- Ask the presenter who analyzed their data for them (even if they have already said they analyzed it themselves).

- Tell the speaker that their method is not valid (but don’t explain why).

- Tell the speaker: “This was a pretty good presentation. When you have been in grad school a few more years I think you’ll be a really good speaker.”

- Tell the speaker that this kind of work has been done before and ask what they have done that is unique.

- Raise your hand to ask a question, but then sit back, squint your eyes, exhale loudly, pause for a moment, then say, “Never mind”.

The Technical Challenge

On multiple occasions, I have had to give a short (10 min) presentation by memory because the slideshow wouldn’t open or advance. I have had poor lighting, or poor color contrasting from the projector, which made it difficult to read my slides. I have had projection screens which were much smaller than I anticipated such that my text was too small to read on figures, and I’ve more or less given up the hope that I will routinely encounter “presenter mode” when using podiums or other people’s machines. I’ve had a projector that kept shorting out during the talk and creating blank screens for 10 seconds, something which you can hear me talk about in the lecture recording but not see on the recorded slides. I’ve had my available time cut in half, had to cut my presentation short because I included too much detail, realized I had poorly organized the presentation of material or forgotten to define a critical aspect, been unable to play videos or animations, had hand-held slide advancers with low batteries, had automatic slide advance turned on by mistake, and more.

When you face these surprises during a talk, you often don’t have the time, never mind the presence of mind, to resolve the problem. You simply have to make the best of it before your time runs out. It helps to know your material, but it also helps to be able to improvise, which is a skill best developed in practice. You might need to fill air time, or reconstruct your presentation on the fly, or make light of the situation to cut the tension in the room. To help my students prepare, I asked them to send me their peer presentation, as I wanted them to use a presentation they had just given and were familiar with. Then, I introduced mistakes into the presentation without disclosing what those might be, only that they would be there.

To think up enough technical problems I could use, I enlisted the help of scientists on twitter. Click on the Tweet below to find the thread and see the other contributions from @HannahMLachance, @canda007, @Wymelenberg, @vaughan_soil, @murphyc1928, @cskrzy, @maria_turfdr, @mcd_611.

I came up with this non-exhaustive list:

- Replace a video with a still shot

- Have 2 students make slides on the same topic, then have them present the other one’s slides (to simulate when a co-author gives you some slides on their contribution and you forget what they mean).

- Reorder some of the slides

- Remove a lot of the text on the slide

- Resize images to be too small for audience to see resolution

- Introduce blank slides to simulate projector connection issues (like screen flickering on/off occasionally)

- Ppt won’t open at all or won’t advance beyond title slide

- Change font on all text to tight cursive

- No ‘presenter mode’ available

- Resize slide dimensions and don’t adjust proportions to ensure fit

- Turn laptop around so can’t see screen as if presenting at a podium

- Add animations to everything

- Add notification of email on timer (created a shape with animated pop in and out, as well as notification chime).

- No photos

- Slide advancer with poor quality batteries

- Automatic slide advance

Public Presentations

Public presentations are an overlooked part of academia, but a crucial aspect. If you are at a public university, or you receive state or federal funding, your work is being supported by tax dollars. Many federal grants require an outreach or public education portion to your project, where you make the results available to interested parties (called stakeholders). Science communication is also extremely important in bridging the divide between scientific and public communities.

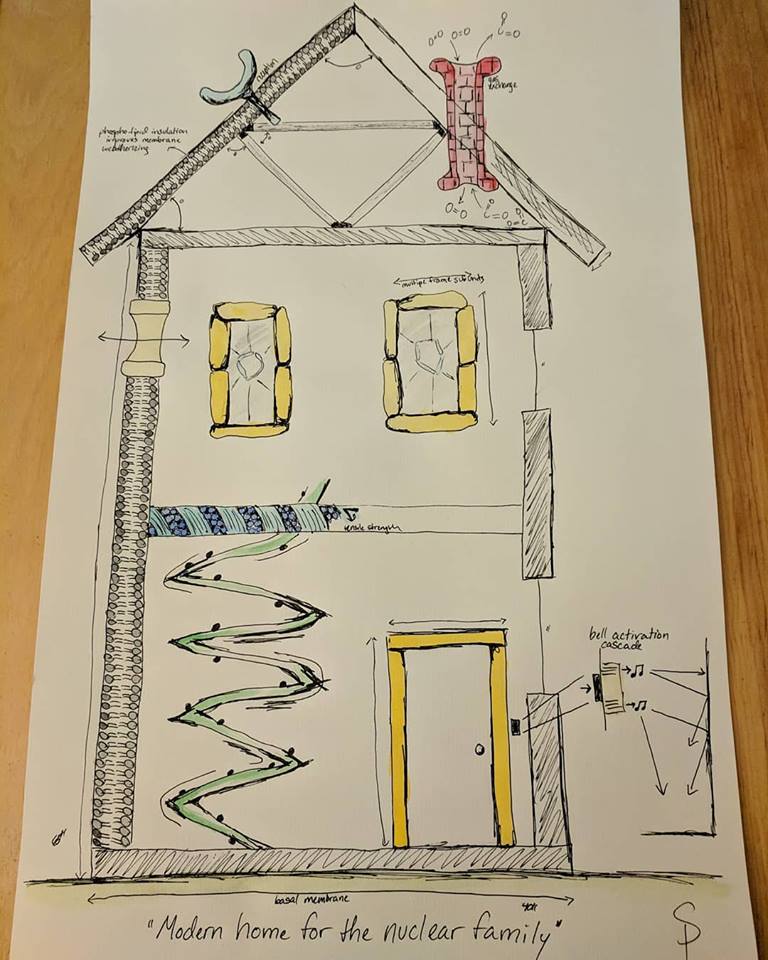

Public presentations need to present information approach-ably. I don’t mean they need to talk down to people, I mean they need to consider that the audience might not have a frame of reference for what you are talking about. I have a PhD, but it’s meaningless if I attend technical lectures on physics. For the third challenge in class, students can give their presentation again but with the knowledge that they can’t throw 20 slides worth of dense information at their audience, they can’t use technical language without defining it, and that sometimes the best way to explain complicated information is using pictures or analogies.

Update: In light of Corvid-19 concerns, campuses have been closing and switching over to remote instruction. This was rather challenging to do well with a presentations class, as giving a webinar isn’t the same as giving a public presentation. To be more creative, I am having students submit their public presentation slides online. I then assign them to another student, who has to annotate the ‘presenter notes’ with the speech of how they would present these slides. I then return the annotated version to the original presenter so they can see how well their slides spoke for themselves. In this “presentation telephone game”, I hope they will see how easy their slides were translatable to someone else, which is a common problem in slides put online without any notes or audio: so much gets lost when the presenter isn’t providing the information and filling in the additional information that is only briefly noted on the slides.

Learning (to Pretend) to Enjoy Giving Presentation

You can’t always control the technical aspects of your talk, or select your audience, or even be prepared for the weather that day. You won’t always be well-rested, or in good health, on the day of. Fun fact about stress, it can trigger spotting or early menstruation. There’s nothing quite as terrifying as being in the middle of your presentation when you are suddenly aware that you have a limited amount of time to get off stage and hope that there are feminine products available for free in the nearest restroom, because your women’s dress pants don’t have pockets for you to carry quarters for the dispensary machines.

You won’t always have time to prepare. Once, I had 5 minutes of notification that I would have to stand up in front of 50 – 75 other college students and Jane Goodall and present a recap on a service-learning course, at a time when I dreaded any and all public speaking. But you can’t really decline the offer to talk in front of Jane Goodall when she had taken the time and effort to be in the room to listen to you all. So you just have to stand up and start talking before you convince yourself you can’t do it.

You can have faith in yourself, know that you will try your best, and remind yourself that it will be good enough. I’ve been an audience member at perfect presentations, and I remember that it went really well and nothing at all about the content. The talks that I remember most are the ones where the speaker connected with me. They were funny, they were humanizing, and they took technical problems and awkward interactions in stride.

The best way to become a better speaker, I think, is to be open to the idea that you are going to mess up. A lot. But each time, you will learn from that experience, you will ask for feedback, and you get back out there. As academics, we have to present information on nearly a daily basis. It is, in fact, a significant part of the job. So instead of dreading it, we should at least pretend to enjoy it until, one day, we find that we do.