The Ishaq Lab is testing out some probiotics in mice this spring, as we look towards the next phase of our broccoli sprouts and gut microbiome work: generating solutions. It has been five years since our last mouse experiments, in part, because we have been busy digging into samples, data, and ideas from those studies.

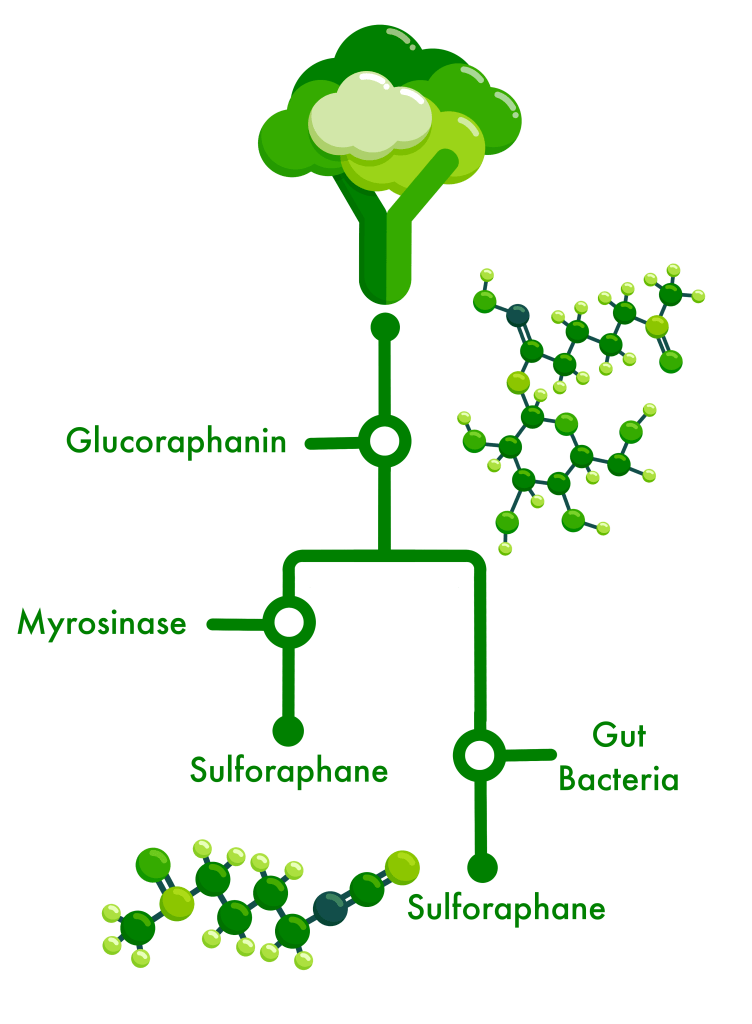

We gained valuable insight into which and how gut bacteria might metabolize the inactive glucosinolates from broccoli sprouts – glucoraphanin being the one we focus on – and produce byproducts like sulforaphane which our gut cells can use to reduce the chemical and physical damage caused by inflammation or oxidation.

This process is easy in the lab and tricky in the real world – not everyone has the bacteria in their gut which can do it, some have the bacteria but they are not active, and some have the bacteria but they are making a different version of the byproduct which we cannot use.

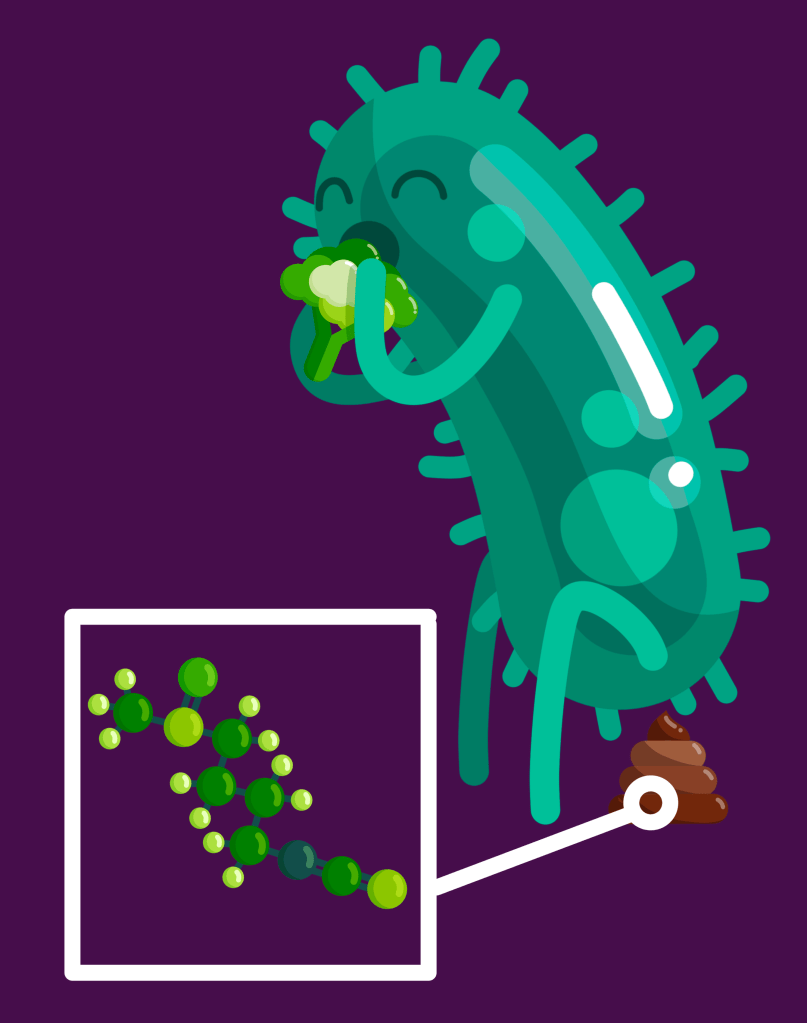

For the past three years, we have been screening >300 gut bacteria to identify and select ones with the ability to grow in the presence of GLR and metabolize it into the byproducts SFN or SFN-nitrile (which can be antimicrobial towards some bacteria).

In culture, the byproducts more-or-less all help the bacteria to survive by providing sulfur, glucose, or other chemicals it needs, but also by acting as an antioxidant compound that binds to a free oxygen (reactive oxygen species) so it doesn’t try to bond with chemicals on the surface of cells and cause them damage (oxidation damage). The byproducts also appear to help the bacteria thrive in acidic culture media which they otherwise can’t survive. When cultured with colon cells and GLR, some of those bacteria and their byproducts reduce inflammation.

The culmination of the past few years of work was to choose two bacterial cultures to try out our idea: that probiotics plus the broccoli sprout diet would help individuals who were not responsive to the diet. Because the gut microbiome, health, and the way that an individual and their microbes respond to diet are all very complicated processes that are specific to each person, it’s easier to test some of these concepts first in the lab or, which we did in early January, in animal models that mimic disease conditions in humans.

We ran a short trial in mice to find out if our two bacterial cultures that were so successful in the lab would also be effective when put back into the chaotic and competitive ecosystem of the gut. To further challenge our bacteria, we tested their ability to survive and reduce inflammation during a flare up of ulcerative colitis.

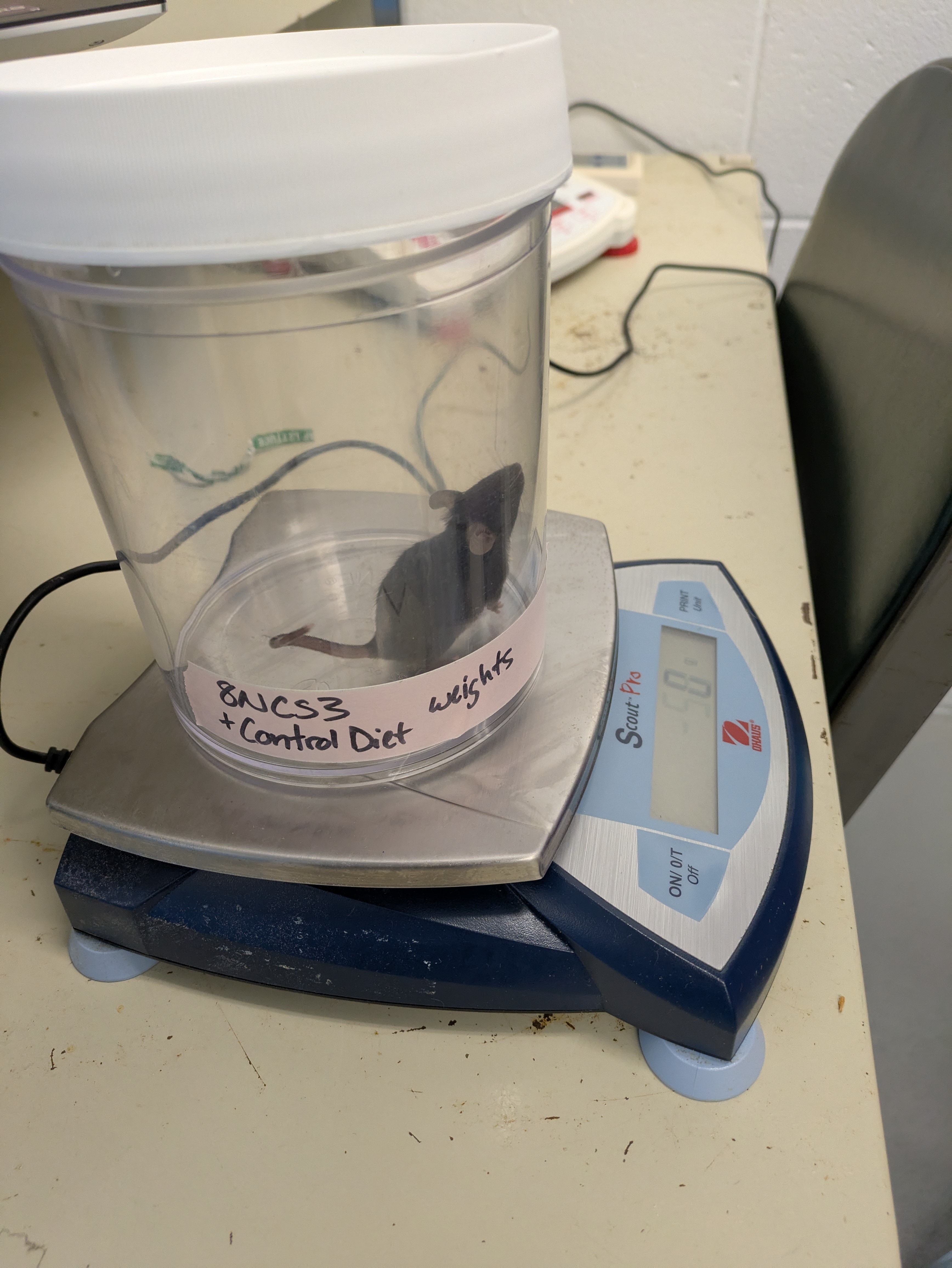

Every day for almost two weeks, we weighed each mouse (shown below) to make sure the colitis did not cause too much weight loss. Sue, Alexis, Johanna, and Ashley were all approved to handle the mice, so we were in charge of picking them up to weigh them. This was no easy task – mice are agile!

Each day, we also collected feces from the cages to check for diarrhea, or for blood, which are two symptoms of colitis. Our undergrads Madison and Brian worked tirelessly to tweeze feces into collection tubes, and to use the FOBT cards to check for blood.

We used custom made gelatin cubes filled with probiotic to deliver our treatments. The gelatin stuck to the side of the cages which allowed us to easily see that our mice were consuming their probiotic.

It will take us months to process some of the samples we collected which are the most cost-effective to run, and the rest will have to wait in the freezer until we receive more funding (which could take months or years as the changes to the federal funding system have doubled the time it takes for proposals to be reviewed and the ~5-20% of accepted projects to receive funding). We collected >500 fecal samples (each with 5 – 10 pellets/sample), 200 gut samples, 100 intestinal tissue samples, and 50 blood samples! To help maximize the benefits of this experiment and use all parts of these mice we also collected samples for a course at UMaine which teaches pre-medical, pre-veterinary, nursing, biology, and other health-focused students how to make and read tissue slides, to better understand anatomy, physiology, developmental biology, and health.

Still, we gained valuable data already, and the experiment provided a unique opportunity for students to receive hands-on-training for evaluating disease intensity using fecal samples, using tissues to make slides for histology, evaluating intestinal damage to tissues, collecting samples using aseptic technique to prevent contaminating them, working safely with microbes, and collaboratively working as a team to advance knowledge of health. Myself and our grad team (Johanna, Alexis, and Ashley) managed the project, and our undergrad team (Madison, Brian, Aaron, and Alexandra) were there to help us label ~1000 tubes for sample collection, and collect hundreds of fecal pellets out of the used bedding so we could track mouse microbes. Undergrads were also able to learn some general mouse care and research facility care from the ‘mouse house’ technician at UMaine, Alexis R. A former UMaine undergrad in the AVS program, Alexis R. manages and cares for a wide variety of animal species and she was instrumental in helping us manage our intensive sample collection schedule.

This project was made possible by the help of many. Again, we are grateful to Alexis and the UMaine CORE staff who not only support research at specialized facilities but helped us to afford to run our pilot project, to Emma who runs the UMaine Electron Microscopy Lab for teaching students histology and microscopy, to all the undergraduate and graduate students who worked tirelessly to help each other on this project, and to the funding agencies which supporting the lab work that helped us get to this project: the Biomedical Association of Maine (graduate awards), the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation (graduate awards), the NIH NIDDK, and the USDA.