My sabbatical – a semester-long release from my teaching, undergraduate advising, and departmental administration duties – wrapped up at the end of December. Despite only having to ostensibly perform half my job, I worked full-time my entire sabbatical just to keep on top of my current workload because university ‘responsibility creep’ is too pervasive. However, being on sabbatical allowed me just enough free time during the work week to reflect in a way that I have not been able to afford in a long time – something avid readers of my blog might have noticed as my introspective content has been sparse and the length of my posts has diminished over the last few years. Case in point: I started the outline for this blog post in November 2024 with the intention of posting in January 2025todiscussmy sabbatical plans for fall 2025, and I am just now getting around to writing the summary of events at the end of January 2026.

What is a sabbatical and who takes over my responsibilities?

A sabbatical is broadly used to describe a long break from one’s job responsibilities, but it is structured very differently based on career and institution. While it can mean an extended vacation bestowed on long-term employees after years of service, university sabbatical provides a temporary release from some responsibilities to allow faculty to improve other parts of their role/responsibilities. For example, many faculty use their sabbatical to visit another lab to launch a collaborative project or learn a new technique, others use it to learn new topics to expand their teaching repertoire. Institutions may set requirements for research or teaching objectives, but at UMaine the faculty propose their own goals in a written application. Faculty are eligible to apply for one or two semesters off every six years of service, and proposals are reviewed by the Department Chair, Dean’s Office, and Provost’s office before some are approved.

For example, UMaine’s guidelines and application for sabbaticals is here. You’ll note that only a certain number of sabbaticals may be approved for each campus in the UMaine system each year, regardless of how many people are eligible. Thus, the application materials (your proposal) are import because, from the UMaine guidelines, “The selection of those who will receive these sabbaticals shall be based on a program proposal which includes a statement of intent and on benefits of the proposed sabbatical to the individual, the campus and the profession.”

Asking for one semester off (4 months) versus two (the 9-month academic year) creates different challenges for one’s department, as my duties don’t vanish when I’m not there. Sabbatical proposals require faculty to describe how our existing responsibilities will be met. My undergraduate advisees needed to be reassigned to my colleagues in the Animal and Veterinary Science program (some of whom had to resolve enrollment and academic admin barriers for 50 undergraduates), I needed to find adjuncts with highly-specialized academic backgrounds to teach my two fall courses (totaling 130 students), and critical decisions still needed to be made to help the program and department survive the university-wide restructuring and budget cuts that stemmed from the year of chaos in federal funding for research and education.

Luckily, my department had room in the budget to hire two adjuncts, because when faculty take one semester of sabbatical off, we still draw 100% of our salary (half of mine is for research, half is for teaching/advising, and we are required to provide departmental administration and university service for free). Thus, I needed to have my sabbatical plan approved in advance by my departmental chair to ensure we had money to hire temporary replacements. If I had taken a year off, my salary would have been reduced by 50% for that year, and the remainer would have been used to pay for a temporary employee to teach/advice 12 credit hours over 9 months.

Of course, some responsibilities cannot be re-assigned or paused, so I was still obligated to perform some teaching, advising, and admin duties even though I was ostensibly freed from those. I reflect on that towards the end of my post, after I talk about my goals.

Sabbatical Goal 1: Flipping AVS 254 Intro to Animal Microbiomes

My primary goal was to transform my existing lecture-based course, AVS 254 Intro to Animal Microbiomes, into a flipped-classroom format in which all lectures are recorded ahead of time for students to watch at their convenience, and the scheduled class time is spent on active learning and completing assignments. I completed this objective, but it took me 7 months instead of 3 because of the extensive burden of generating curriculum (literature review, summarizing info, finding or creating images and diagrams, making content visually accessible, writing presenter notes for all slides, finding journal articles which were easy to read for homework, designing walk-through assignments which teach research skills). Flipping the classroom can benefit the students, by providing more opportunities to connect learning material with skills and problem-solving. I also needed much more time than expected to complete my objectives because of the teaching and advising which couldn’t pause during my sabbatical.

Flipping the classroom made better use of my time and expertise by allowing problem-solving assignments. While it takes extensive expertise to complete the literature reviews and summaries for my lectures (which are each on a different topic), reciting the content of my lectures each year is not a good use of my time. Instead, recording my lectures allows me to use classroom time to provide my expertise to students on assessing and using information on microbes to solve problems. In previous years, I flipped several lectures and use class time for active learning, which was very successful. For my sabbatical, I revised all the course assignments from at-home writing to in-person research-based activities: how to use databases to analyze microbiome data and compare DNA sequences, compare existing data on microbiomes and interventions, choose one technology versus another, design hypothetical experiments or interventions, and generate action plans for hypothetical collaborations. The flipped classroom creates asynchronous learning of course material, which is also part of a long-term revision to the modalities of my course that I’ve been working towards for several years. Last year, and starting again next year, I will offer my course with an in-person version (the flipped classroom), and as an asynchronous version.

Recording content allowed me to improve depth of material. To condense the material from three lectures per week into two per week (or one/holiday week), I restructured my 35 lectures into 28. This involved moving content rather than cutting it, and allowed me to condense similar material into one lecture instead of dispersing it to work within the time limit of in-person courses. By recording lectures, I was able to double the amount of content provided and go into more depth without increasing total lecture time, because the recordings proceed faster than live lectures. For example, in a lecture on how diet affects microbial communities in monogastric animals, I was able to add comparative anatomy, physiology, microbiology as well as integrate more biophysics of digestion, and collectively this allowed me to tie science from multiple disciplines into a cohesive narrative about how host species and diet both affect gut microbes.

Recording content allowed me to make materials more accessible. First, no matter how I structure my content, some students feel like there is too much material while others feel there is not enough. To provide a “Goldilocks Zone”, the recordings can be played at low or high speed to keep pace with their learning style. Second, no matter how many students indicate they want in-person courses, only about 1/3 are able to show up the entire semester, and that falls to 1/10 every time (according to students) a science “weeder course” has an exam as students are given little-to-no flexibility on deadlines for those courses and are forced to de-prioritize (and risk failing) another course. I’ve spoken to students who have said they chose to skip assignments or accept a worse grade in my course instead of falling behind in chemistry because they knew I would let them turn in assignments weeks or even months late while they receive little flexibility for life events which prevent them from attending class/lab or completing assignments on time. To combat this, all my recorded lecture content is available at the beginning of the semester for students who need to complete this course at custom intervals instead of weekly. The asynchronous version accommodates students who have too many courses, work, long commutes, medical constraints, family care duties, or other obligations which preclude them attending and engaging with the course. This, too, presented a challenge as I needed to create protocols or walkthroughs which can be accomplished within the classroom as well as online, and make them expandable to create extra objectives for students completing assignments in a group to maintain equitable workloads with online students completing assignments solo.

Recording the lectures required an overhaul of all materials to make them higher quality, self-explanatory, and to make them more inclusive to learning assistance technology. In addition to generating more content, all slides needed to be recorded which required presenter notes/ a script to improve the quality of the recording and reduce the use of filler words. To improve content for non-visual learners (visual disability or those who listen to the audio recording at work without looking at the slides, this also required a significant time investment to describe each graph, diagram, or other visual element in my presenter notes/audio recording. By adding presenter notes on slides, I could also create annotated PDFs versions of lectures that are easier for students to use with screen-readers, and easier to download for students with low-quality internet, and allows students to have a written script for the video version as the subtitle-generating AI in Kaltura sometimes struggles to accurately transcribe scientific terms or certain words because of the way I speak.

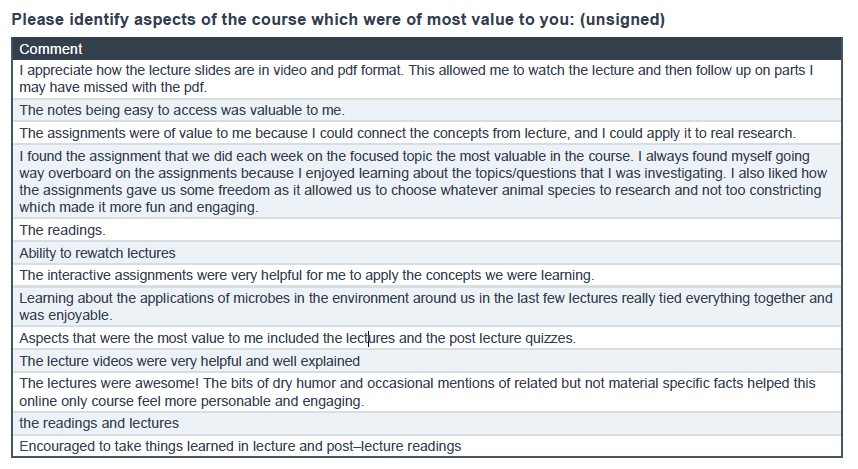

Students were enthusiastic about the updates to the course content and format, based on course evaluations from Fall 2025 when an adjunct taught my course but I was making course revisions in advance of releasing course material each week. Student comments included:

- “I loved that this course was offered online. As a dual–enrolled student, this made it possible for me to take the course. I also really appreciated the flexibility of deadlines. I feel that it was very reasonable to simply ask for more writing if the assignment was late. Thank you!”

- “I appreciate how the lecture slides are in video and pdf format. This allowed me to watch the lecture and then follow up on parts I may have missed with the pdf.”

- “I found the assignment that we did each week on the focused topic the most valuable in the course. I always found myself going way overboard on the assignments because I enjoyed learning about the topics/questions that I was investigating. I also liked how the assignments gave us some freedom as it allowed us to choose whatever animal species to research and not too constricting which made it more fun and engaging.”

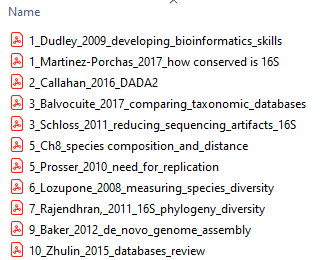

Sabbatical Goal 2: Updating course materials for data analysis

The second goal for my sabbatical was to update the course materials for my data-analysis based AVS 454/554 DNA Sequencing Data Analysis Lab. Unfortunately, I did not even get to begin this objective because of the extensive effort to revise AVS 254 and my persistent workload was too high. However, I did receive useful feedback from the adjunct instructor who taught my course while I was on sabbatical. This data analysis lab uses coding in several programs to analyze DNA sequencing data and generate draft manuscripts. Updating the materials would benefit me by making this course cutting-edge and streamlined, as these programs, and the theory behind the data analysis workflow, evolve on an annual basis in the rapidly changing field of microbial ecology. The feedback I received indicated that graduate students needed more remedial content, especially a basic understanding of statistics and a more thorough explanation of how to apply those statistics to their experiments and microbial community analysis. As such, when I can update this course, I will expand my existing 4 lectures on statistics to 6.

Sabbatical Goal 3: Catching up on research

My third sabbatical goal was to catch up on my tasks for completed and in-progress research, as well as to add new components to my work, which I successfully completed. My research on how broccoli sprouts in the diet can induce gut microbes to reduce inflammation has been adding new facets over the past year which require more of my attention, including metagenomics, whole genome sequencing, transcriptomics, protein identification and enzyme isolation, and probiotic development.

My sabbatical allowed me the time to write/revise seven scientific manuscripts for peer review, provide three presentations of my work to research and student audiences, to help one of my graduate students write their PhD dissertation in preparation for their defense, to help one of my students prepare for and take their comprehensive, to provide graduate committee support for two students to defend and another to take their comprehensive exam, and to plan/perform an intensive probiotic trial in mice. In addition, I spent the fall revising three large-scale, multi-year, multi-institution funding proposals to USDA NIFA and NIH.

I was also able to complete more research administration and leadership opportunities, such as fostering research case studies through my role on the Microbiome Stewardship research group, leadership duties for the Microbes and Social Equity working group, an international research society, and participating in research-curation initiatives such as the creation of a Microbe Specialist group for the IUCN.

My teaching was reallocated during my sabbatical, but course revision was more intensive than previous years

I teach 2 courses each semester, three of which are required for AVS undergraduates, and one of which teaches a specialized data analysis to graduate students which need it to perform their research. Luckily, I was able to find local expertise for my two fall classes, which are highly specialized topics and difficult to find replacements for in Maine. My data analysis course was taught by a faculty member in the bioinformatics master’s program at UMaine, who has significant experience teaching coding for data sciences. My animal microbiomes course run by one of my PhD students, Ashley, who was a grader for the course last year and had gained familiarity with the content and delivery of the course. To help her manage the 97-undergrad course, it was held in an asynchronous format, in which all lectures were pre-recorded by me and students could access content and complete assignments at their convenience each week.

However, this year’s course was a challenge for both of us: I was actively revising the lectures, reading list, and assignments during the semester in an effort to keep pace with the overhaul objectives of my sabbatical. I had intended to revise at least half the source over the summer, when I was without summer salary and ostensibly should not have been working, but I had so many service (unpaid), research, and advising activities, as well as the course revision, that I worked full-time all summer. I was able to revise most of the first third of the course over the summer, which bought me time in September and October when I was still working full – or more than full—time despite being on sabbatical: the amount of service, advising, and research once again overwhelmed my schedule. In addition, I had to spend September and October revising two large-scale, multi-year, multi-institution funding proposals because of the deliberate delays to the USDA NIFA and NIH research funding mechanisms in 2025 delayed reviews on previously submitted proposals, and for the USDA funding, pushed proposal submission deadlines from the summer to the fall. Thus, by November I was rushing to revise course content to stay ahead of the syllabus.

Despite being off contract (unpaid) all summer, and despite being on sabbatical and freed from teaching and advising and admin all fall, I put in 40 hours a week on course revisions, evaluating graduate student performance in comprehensive exams and defenses, writing recommendation letters for undergraduates and graduates, oh, and teaching and assisting with departmental administration. That’s right, I taught 4 students during my sabbatical going through their Capstone courses out of sync to help them graduate. And, because of the university strategic revising evaluation (we got marked down for having too high of a student: faculty ratio even though the university has not given us permission to hire more faculty despite our increasing enrollment in the last 5 years) and subsequent requests to slash departmental budgets (without reducing our workload or number of students), I attended hours of administrative meetings and helped write a plan for our program in response to the SRE.

My advising was reallocated during my sabbatical, except for all the unpaid advising university faculty typically do

The sabbatical provided temporary relief to my heavy workload and a chance to catch up a little, but by no means did it resolve the burden of increased responsibilities, as enrollment or student needs increase but the number of faculty per student does not. In fact, being on sabbatical allowed me to work at a sustainable 40 hours per week instead of the 50+ hours per week I am pressured to work every semester through the number of student, colleague, and university requests for my help. Yet, during my sabbatical, I still had advising and teaching that could not be re-allocated, and departmental activities still needed effort, such as making decisions about spring courses or providing timely information to the university due to the strategic revisioning plan. I bring this up as a way to demonstrate how valuable sabbaticals are and re-enforce the support for sabbaticals at the college level. I urge the university to find creative ways to allow faculty to extend their sabbaticals to one full academic year without having to take the full-year-sabbatical reduction in pay.

The changes to federal education and research funding, as well as the overall economy, changed academic timelines for many students. In 2025, I advised three graduate students, and was on the thesis committee for two more, who needed to graduate sooner than expected due to federal delays in graduate research fellowships which left them without salary. Similarly, my previous advisees needed letters of recommendation to apply for veterinary or medical programs, or jobs. I wrote 13 letters (totaling 13 hours) this summer (when I am off contract) and fall. This fall, I had 4 students who needed to take the AVS Capstone courses to graduate on time, so I was still performing some teaching tasks (paid through add comp). This has become a regular occurrence as, based on student feedback, the reduction in faculty at UMaine has reduced available courses and made enrollment much more difficult – essentially, I am asked by students to teach my courses out of their designated semester because they need help to graduate early because they cannot afford another semester. Students need more flexibility in their course availability and they need help year-round, and providing summer salary or sabbaticals offers faculty a way to accommodate students while still accomplishing our other tasks.

My sabbatical was an incredible opportunity

For anyone who is considering a sabbatical, I absolutely recommend it. You don’t need to make grand plans, or do something completely novel, or even resolve your entire pile of unfinished business for your sabbatical to be successful. View it as a “stay-cation”, and a way to check the 1000 tiny items off your to-do list that couldn’t be accomplished because of the perpetually hectic pace of academia. If you think you are too busy to take a sabbatical, then you really need to. It may seem like I wasted my sabbatical on work or old, unfinished business, but it allowed me to free myself from lingering obligations, make improvements to teaching or advising to make my job run more smoothly, and importantly, it helped me gain back some time to think and write which are critical aspects of my job that continuously get de-prioritized by urgent requests for my time (meetings, emails, and having to drop everything and work on requests for information from the college). And, I had more time to paint in 2025 than I have had in years. I will have to wait 6 years to be eligible for my next sabbatical, but I’m already looking forward to it!